Author

VIDEO OF THE WEEK!

Psy and Snoop Dog just did a video together. Why are we covering this? Psy and Snoop just did a video together!

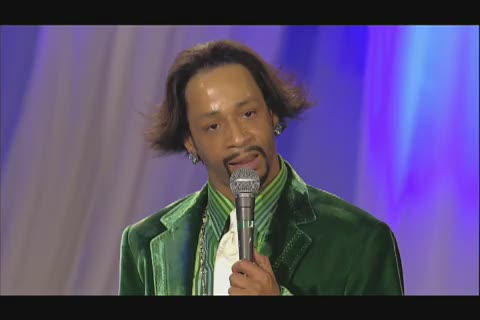

KATT WILLIAMS TALKING ABOUT WEED.

NEED WE SAY MORE?

CORPORATIONS AND MARIJUANA: LEGAL WEED GOES MAINSTREAM

Americans could learn from Canada, as the New York Times explains in When Cannabis Goes Corporate. Canada’s free-for-all approach prompted complaints from police and local governments, so Canada adopted a regulated system for growth and sales. Enter Tweed Marijuana, one of the companies licensed to grow medical marijuana in Canada.

The new rules allow prescription holders to buy from approved, large-scale, producers. More informal growing operations suffer. But the changes have spawned an industry of more legitimate producers with bigger business models. And that should mean more sales.

Canada expects to collect taxes on over $3.1 billion in annual sales. The figures stateside could be vastly better. In Washington State, where even recreational marijuana is now legal, the Liquor Control Board hired Prof. Mark Kleiman of UCLA to research the state’s marijuana market. He estimated Washington’s medical and illicit consumption generated approximately $1.2 billion in sales annually.

Medical marijuana neon sign at a dispensary on Ventura Boulevard in Los Angeles (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Colorado too voted to legalize marijuana even for recreational use. Already, Colorado gets $2 million from marijuana taxes. And while there are rules in Colorado and Washington, both states seem well on their way to regulating and profiting from the industry. Medical use is far more prevalent, now numbering 20 legal medical marijuana states and D.C.

Yet in the Feds’ view, regardless of state legality, marijuana is a controlled substance and illegal under federal law. As more states have clashed with federal law, this mismatch has become more contentious. The Department of Justice issued a response suggesting that it will lay off the raids and prosecutions.

But the feds will lay off only if the states create “a tightly regulated market” with rules that address federal “enforcement priorities” such as preventing interstate smuggling, diversion to minors, and “adverse public health consequences.” Those phrases seem imbued with discretion. This memo to U.S. attorneys makes clear that the DOJ can still prosecute growers and sellers.

To be sure, this is much bigger than a tax problem. And yet the tax problems of the industry are huge and are thought to be one of the industry’s major impediments. Section 280E of the tax code denies even legal dispensaries tax deductions. The main culprit is Congress, not the IRS. The IRS has said it has no choice but to enforce the tax code passed by Congress.

How big is the industry’s problem? “The federal tax situation is the biggest threat to businesses and could push the entire industry underground,” the leading trade publication for the marijuana industry reported. One answer has been for dispensaries to deduct expenses from other businesses distinct from dispensing marijuana. If a dispensary sells marijuana and is in the separate business of care-giving, the care-giving expenses are deductible. If only 10% of the premises are used to dispense marijuana, most of the rent is deductible.

Another idea is for marijuana sellers to operate as nonprofit social welfare organizations. That way Section 280E shouldn’t apply. The industry needs to operate more like other businesses. Sometimes such matters involve structural questions. To avoid trouble with the IRS, some claim that dispensaries should be organized as cooperatives or collectives.

The Marijuana Tax Equity Act would end the federal prohibition on marijuana and allow it to be taxed. The bill would also impose an excise tax on cannabis sales and an annual occupational tax on workers in the growing field of legal marijuana.

(Thanks to reporter Robert Wood and Forbes magazine for this post.)

POT VENDING MACHINES

Washington State is considering including pot vending machines in their retail stores! The self-serve machines are being touted as “convenient for customers who don’t want to wait in lines, and for those who are particularly shy.”

THE TIDE HAS TURNED

Great article from Josh Voorhees, our favorite SLATE contributor

Courtesy of Slate –

An overwhelming majority of Americans believe that the legalization of marijuana is inevitable. We’ll soon find out if they’re right.

Voters in Alaska and possibly Oregon will decide this November whether their states will join Colorado and Washington in legalizing the commercial sale and recreational use of pot. Similar initiatives are at varying stages in more than a half-dozen other states—Nevada, Arizona, and California among them—where advocates are looking toward 2016, when they hope the presidential election will turn out enough liberals to push those efforts across the finish line. All told, more than 1 in 5 Americans live in states where marijuana use has a legitimate chance to become legal between now and when President Obama leaves office.

It’s not just at the ballot box where the pro-pot crowd is putting points on the board. Lawmakers in at least 40 states have eased at least some drug laws since 2009, according to a recent Pew Research Center analysis. According to the Marijuana Policy Project, proposals to treat pot like alcohol have been introduced in 18 states and the District of Columbia this year alone. Meanwhile, 16 states have already decriminalized marijuana, according to the pro-pot group NORML—Maryland will become the 17th in October. In large swaths of the country getting caught with a small amount of weed at a concert is now roughly the same as getting a speeding ticket on the way to the show. While not leading the charge, the Obama administration is allowing states the chance to experiment. The feds have given a qualified greenlight to Colorado and Washington to dabble in recreational weed, and have even taken small steps to encourage banks to do business with those companies involved in the quasi-legal pot trade.

Given this momentum, it’s not difficult to see why 75 percent of Americans—including a majority of both those who support and those who oppose legalization—told Pew pollsters in February that they now believe it’s a matter of when, not if, the nation’s eight-decade-long prohibition of pot ends. The question is: Are they right?

This moment isn’t the first time that the United States appeared on the cusp of legalization. After steep gains in popular support during the early and mid-’70s, support for legalization climbed to 30 percent in 1978, only to plummet back into the teens the following decade as Baby Boomers became parents and Jimmy Carter’s pro-decriminalization administration gave way to Ronald Reagan’s war on drugs. “This was supposed to be inevitable then,” says Kevin Sabet, a legalization opponent and former Obama drug policy adviser who helped found Smart Approaches to Marijuana after leaving the administration. “No one could have predicted that [support]would have been wiped away so quickly.”

The pro-pot crowd isn’t ready to declare victory either. Ethan Nadelmann, who heads the Drug Policy Alliance and has spent decades in the reform trenches, says he’s of two minds when he thinks about the future. “On the one hand we have this extraordinary momentum,” he says. “On the other, public opinion can be fickle and marijuana is not going to legalize itself.”

While such caution is reasonable, it’s obvious that things are different now than they were 40 years ago, when then-record levels of support for legalization were good for little more than a vocal minority. It wasn’t until 2013 that a majority of Americans said for the first time that they supported making it legal to use weed. Support now stands at 54 percent in the most recent Pew poll, 23 points above where the legalization effort stood as recently as 2000 and 13 points higher than in 2010. Even those fickle Baby Boomers are back on board, with 52 percent now in favor—5 points more than that generation’s 1970s-era high. Meanwhile, each passing year brings us an electorate more familiar and less fearful of marijuana.

It’s not just a matter of shifting demographics. There’s also the fact that voters have increasingly gotten an up-close look at state-legal weed in the form of medical marijuana. Twenty-one states and the District of Columbia have legalized pot for medicinal purposes to varying degrees since California became the first to do so almost two decades ago. Voters in Florida are set to decide later this year whether they want to join that group, something that would give advocates their first voter-referendum victory in the South. (Florida law requires at least 60 percent support, however, making it a heavier lift than it has been in other states.)

Some pot opponents warn that medical marijuana serves as a Trojan Horse for the larger legalization movement, but that argument relies on Americans believing that the dangers of possibly legalizing recreational weed tomorrow outweigh the benefits of actually prescribing it to cancer patients and others in need today—a viewpoint shared by a diminishing number of Americans. While 54 percent of respondents told Pew they thought “the use of marijuana” should be made legal, things were more complicatedwhen the question changed from a simple yes-or-no to one where people were asked to pick between three choices: 39 percent said that pot “should be legal for personal use”; 44 percent said it “should be legal only for medicinal use”; and 16 percent said it “should not be legal.” Still, the answers to the original question—“Do you think the use of marijuana should be made legal, or not?”—suggests in an all-or-nothing environment, most Americans choose the former.

Regardless, medical marijuana has already served as stepping-stone for states that have or are considering regulating the sale and use of recreational pot. In Colorado, where retail stores opened their doors on New Year’s Day, advocates were able to point to the state’s tightly regulated medical market, approved by voters in 2000, to allay fears that the state couldn’t regulate a marijuana market from scratch. To date, Colorado regulators have delivered on those promises, building a relatively hiccup-free commercial market on the back of the medical marijuana industry. (Things in Washington, where the medical market is unregulated, have proved a good deal more complicated. Residents are still waiting for the first retail stores to open 19 months since the 2012 vote.)

Medical marijuana has become so relatively uncontroversial that late last month the House of Representatives shocked almost everyone when a bipartisan majority voted to block the Drug Enforcement Agency from pursuing medical marijuana operations that are legal under state laws. “Watershed is probably too strong of a word,” says Nadelmann of the unexpected vote for a bill that had repeatedly stalled in the same chamber for the last decade, “but it was pretty close.”

Legalization in theory is different than legalization in practice, and an unforeseen disaster in Colorado or Washington—be it from the production of hash oil or the next time a New York Times columnist overindulges in baked goods—could always affect public opinion. Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper, a Democrat who opposed his state’s 2012 legalization initiative, for one, has warned his fellow governors to take a wait-and-see approach to their own state’s legalization efforts. But it’s looking increasingly like the voters may not be so patient if given the choice.

ARE YOU BAKED? WATCH THIS

If someone told you five years ago that the fastest growing site in the world featured 6 second videos, you’ve said they were high. They weren’t. But you should be. Then watch the above clip.

Cannacon 2014

Higher Ground hit the floor at CannaCon, one of the World’s largest cannabis conventions for businesses, growers and the public. Here’s a virtual tour!

- ‹ Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3